Moving sheets, tiles, bags, tools, and awkward loads to an upper level is where job sites quietly rack up injuries and near-misses: overreaching on ladders, dropped objects, uncontrolled loads, rushed set-ups, and poor landing zones.

A ladder lift and a construction hoist can both reduce carrying on stairs and ladders. The safer choice depends on what you’re lifting, how often, how high, and what your site can realistically support (space, ground conditions, access, weather, and supervision).

This guide walks through how to choose between the two options using practical Sydney job scenarios, simple checks, and clear “stop and reassess” triggers.

First, what are you comparing?

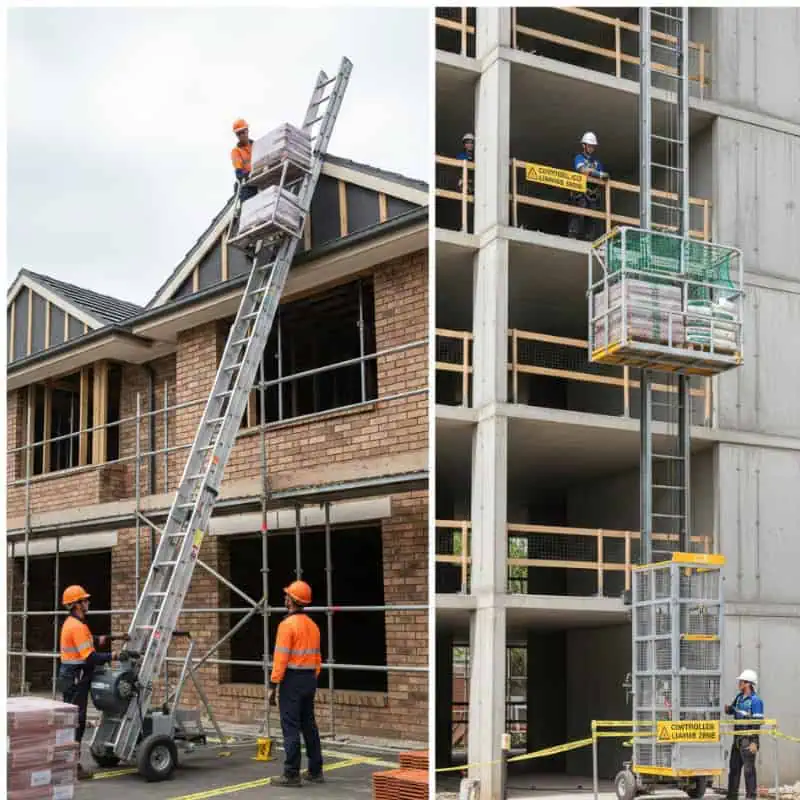

A “ladder lift” (often called a ladder hoist) typically moves materials up a ladder-like track set on an angle, using a carriage/platform. It’s commonly used where access is tight and you need a quick way to move items up to a roofline or upper storey.

A “construction hoist” (site hoist / materials hoist) generally provides more capacity and stability for repeated lifting, often with a more structured set-up designed for frequent, controlled vertical movement.

You don’t need to memorise definitions to choose safely. You need to match the equipment to the risk.

The safest option is the one that best controls these risks

When you’re deciding, think in five risk buckets:

1) Manual handling and fatigue

If the job involves lots of repetitive carries, awkward shapes, or heavy loads, fatigue builds quickly and shortcuts follow. The safer option is the one that most reliably reduces hands-on carrying without introducing new instability or pinch-point risks.

2) Dropped objects and falling loads

Anything moving above people, vehicles, glazing, or public areas (common in inner-Sydney) needs tight controls: exclusion zones, controlled landing areas, and good load restraint. A system that feels “quick” but has poor load control is usually the wrong call.

3) Set-up stability

Most incidents happen because the base isn’t stable, the track/structure isn’t secured as intended, the ground changes during the day, or the landing area is improvised. Choose the option your site can set up correctly every time.

4) Load rating and real-world weight

The risk isn’t just exceeding a load rating. It’s uneven loads, dynamic movement (start/stop), wind gusts, catching edges, and workers trying to “help” a load that’s snagging. The safer choice is the one that keeps you well inside limits and controls the lift path.

5) Weather and environment

Sydney weather can flip quickly—gusty afternoons, sudden showers, and coastal corrosion in areas closer to the water. Wind and wet surfaces can turn a manageable lift into an uncontrolled one. Choose the option with the most predictable behaviour under your actual conditions (not ideal conditions).

Quick decision guide: when each option tends to suit best

Ladder lift tends to suit when

- The site has tight access (narrow side paths, terraces, limited laydown)

- Loads are lighter and more compact (but still awkward enough to justify mechanical help)

- You’re feeding materials to a roofline or upper storey where a track angle makes sense

- The lift is intermittent rather than constant all day

- You can establish a clear exclusion zone and a controlled landing handoff

A construction hoist tends to suit when

- You’re moving heavier loads, bulkier materials, or pallets/cages (depending on model)

- The lift is frequent and planned as part of site logistics (not just “as needed”)

- You need repeatable, controlled cycles with less reliance on manual handling at the landing

- The site can support the footprint, set-up, and safe operating area

- You want more headroom against load limits and job variability

If you’re still unsure, it helps to read the key differences in capacity, controls, and set-up expectations in the product information for your site’s context. You can learn about materials hoists for building sites and compare that to ladder lifts for moving materials up levels to get a clearer picture of what fits your job constraints.

Q: Is a ladder lift safer than carrying materials up a ladder?

If it’s set up correctly, used within its load rating, and operated with a controlled landing zone and exclusion area, it can be significantly safer than manual carrying—especially for awkward items that tempt workers to climb while holding a load.

But it’s not automatically safer. A poorly secured track, unstable base, rushed loading, or people walking under the lift path can erase the benefit fast. The “safer” option is the one you can set up and control properly, every time.

The four numbers that usually decide the answer

1) Maximum lift height you need

Ask: are you lifting to a single roof edge, a second storey, or repeated levels? The more height you add, the more important stability, load control, and predictable stopping become.

2) Typical load weight (not the lightest load)

Weigh or estimate the loads you’ll lift most often. Don’t choose based on the lightest item on the list. Include packaging, moisture (wet timber, wet sand/cement bags), and attachments (platforms, cages).

3) Frequency of lifts

Ten lifts a day is different to seventy. Higher frequency increases fatigue and increases the chance of “just one quick lift” outside the plan. Frequent lifting usually favours the option that’s easier to operate consistently with fewer improvised steps.

4) Site footprint and set-up reality

Some sites can’t support a larger footprint without blocking access, clashing with deliveries, or pushing the lift path over public space. Other sites have room but no stable base area. Be brutally honest about what your site can support.

Sydney-specific realities that affect the decision

Tight access and narrow lot lines

Inner-west terraces, Eastern Suburbs blocks, and many renovation sites have limited side access and minimal laydown areas. Ladder lifts often fit better where a full hoist footprint and exclusion area would interfere with the job flow.

Public interface and neighbouring properties

Working close to footpaths, driveways, or neighbouring boundaries raises the stakes for dropped-object controls and clear exclusion zones. Your lift plan needs to keep the path predictable and keep people out of it.

Wind exposure and afternoon gusts

Sydney can be calm in the morning and gusty later—especially on exposed ridgelines, near coastal areas, or around high-rise wind tunnels. Wind changes how loads behave on an angled track and can make sheet materials act like sails.

Wet weather and slippery landing zones

A damp landing area plus rushing can create slips, sudden load shifts, and awkward catches. The safer option is often the one that reduces “hands-on wrestling” at the landing.

Q: What does SWL mean, and how should you use it on site?

SWL (Safe Working Load) is the maximum load the equipment is designed to lift safely under specified conditions. On site, you should treat SWL as the top edge you do not approach—especially when loads are awkward, uneven, or affected by wind.

Safer practice is to build a buffer:

- Keep typical loads comfortably below the rated limit

- Avoid “one-off” heavier lifts that tempt exceptions

- Consider how the load behaves (flexing sheets, swinging bundles, snagging edges)

If your day includes frequent “close to limit” lifts, it’s usually a sign you need a different method or configuration.

Set-up: where safety is won or lost

Ladder lift set-up essentials

A ladder lift can be a great solution, but the setup has to be disciplined:

- Stable base area (no soft fill, no shifting pavers, no improvised packing that can move)

- Track angle and support consistent with the manufacturer’s guidance

- Securing and stabilising so the system can’t shift during operation

- Clear lift path (no overhead obstructions, no snag points)

- Controlled loading area and controlled landing area

- Exclusion zone so nobody walks under the lift path

Construction hoist set-up essentials

A hoist set-up typically expects more deliberate planning:

- Suitable ground conditions and a clear footprint

- A defined operating area and landing zone

- Controls to prevent unauthorised access

- Routine pre-start checks and documented inspections were required

- A lift plan that fits deliveries and material staging

For NSW-specific safety guidance relevant to hoists and erection hoists, the NSW Government’s dogging and rigging guide includes practical safety considerations and example pre-use checks: erection hoists and mast climbers — safety guidance.

Q: Do you need an exclusion zone around a ladder lift or hoist?

In practical terms, you should plan one whenever there’s a risk of people being under a suspended or moving load, or where a dropped object could land.

On busy Sydney sites—especially renovations—this often means:

- Choosing a lift path that doesn’t cross walkways

- Controlling who can enter the loading/landing areas

- Timing lifts to avoid trades moving through the zone

- Making the exclusion clear and enforced, not just “assumed”

Scenario guide: what tends to be safer for common jobs

Roofing renovation on a tight suburban block

Often safer choice: ladder lift

Why: angled track to roofline, reduced carrying up ladders/scaffolds, fits tight access

Watch-outs:

- Sheets can catch wind—plan for gusts and stop-work triggers

- Keep the landing organised so workers aren’t grabbing unstable loads near the edges

- Ensure nobody is under the lift path

Moving bricks/blocks repeatedly to an upper level

Often safer choice: construction hoist (if site suits)

Why: frequent lifting, heavier loads, repeatable cycles

Watch-outs:

- Overloading is common when the day gets busy—plan load limits and staging

- Keep landing zones clear to avoid “stacking hazards” and rushed unloading

Solar panels on a roof (light but awkward and sail-like)

Often safer choice: depends on exposure and control

- A ladder lift can work well if you can control wind exposure and handling at the landing

- A hoist may be preferable if it provides better load control and less manual wrestling at the edge

- Key is planning: wind checks, secure handling method, and a calm landing process.

Internal renovation with stair access but high manual handling risk

Often safer choice: whichever reduces carrying without creating new hazards

If the site can’t support a safe external lift path and exclusion zone, the answer may be rethinking staging, breaking loads down, or altering delivery timing. The “right” choice is sometimes logistics, not equipment.

Pre-start checks you can actually use (without turning it into paperwork)

Before the first lift of the day

- Confirm the lift path is clear (overhead obstructions, snag points, public interface)

- Confirm base stability and set-up condition (no movement, no settling, no makeshift changes)

- Check controls and emergency stop behaviour (if applicable)

- Check the platform/carriage, ropes/cables, fasteners, and visible wear points

- Confirm landing zone is ready (clear space, good footing, no clutter at edges)

- Confirm exclusion zone and a simple communication method (who is in charge of the lift)

During operation

- Keep loads balanced and restrained as intended

- Don’t “help” a snagging load by pulling from unsafe positions

- Don’t lift over people

- Stop if conditions change (wind, rain, ground movement, site congestion)

Q: What are the biggest mistakes that make a “safe lift” unsafe?

These come up again and again:

- Choosing based on speed instead of control

- Pushing close to load limits because “it worked last time”

- Improvised base packing or set-up shortcuts

- People are walking under the lift path because the zone isn’t controlled

- Landing-zone chaos (clutter, slippery surfaces, edge exposure)

- Using the lift when the wind turns sheet materials into sails

- No single person is coordinating the lift when the site is busy

Stop-work triggers: when to pause and reassess immediately

These are simple on purpose—if any occur, stop and reset:

- The base or track/structure moves, settles, or feels unstable

- The load swings, snags, or can’t be controlled predictably

- Wind gusts make sheet materials flex, lift, or act like a sail

- The landing zone becomes cluttered or slippery

- You can’t keep people out of the lift path

- The equipment shows visible damage, unusual noises, or control issues

- The “typical load” is creeping up toward the rated limit

Choosing with confidence: a practical checklist

Use this to make a decision on a real job:

Pick a ladder lift if most are true

- Tight access is a major constraint

- Loads are moderate and manageable within a comfortable safety buffer

- You can secure the setup properly and keep it stable

- You can create and enforce an exclusion zone

- The landing can be controlled (especially at roof edges)

Pick a construction hoist if most are true

- Loads are heavier or bulkier, or you’re lifting frequently

- Predictable control and repeatable cycles matter

- The site can support the footprint and operating area

- You want greater headroom against load limits and variability

- You’re planning lifting as part of site logistics, not just “as needed”

To sanity-check your choice against real equipment capabilities, it helps to compare materials hoist features alongside your typical loads, lift height, and site footprint.

FAQ

Is a hoist always safer than a ladder lift?

No. A hoist can be safer for frequent or heavier lifting and more controlled cycles, but only if the site can support a correct set-up and controlled operating area. A ladder lift can be safer on tight-access jobs if it’s stabilised properly and the landing/exclusion zones are well controlled.

Can I use a ladder lift in windy conditions?

Wind is a major risk factor, especially for sheets and anything that behaves like a sail. If gusts make the load unpredictable, it’s a stop-work trigger. Plan lifts around the weather and avoid forcing it “just to finish the day”.

How do I reduce dropped-object risk during lifting?

- Keep people out of the lift path (exclusion zone)

- Restrain and balance loads properly

- Keep the lift path clear of snag points

- Keep the landing zone organised so unloading isn’t rushed or improvised

What should I do if loads keep snagging on the way up?

Stop and reassess. Snagging leads to uncontrolled pulling and awkward positions. Check the lift path, the set-up angle, load restraint, and whether the method is right for the shape of the load.

What’s the safest way to move materials to a second storey on a renovation?

It depends on access, footprint, and load type. Many Sydney renovations favour ladder lifts because they fit tight access and roofline delivery, but only if you can set up safely and control the landing area and exclusion zone. For heavier or frequent lifts, a hoist may be a better fit if the site can support it.

Do I need to plan a landing zone, or can we just “grab it when it arrives”?

Plan it. Most handling injuries and near-misses happen at the landing: awkward grabs near edges, clutter, slips, and rushing. A controlled landing zone is a core safety control, not an optional extra.