Belt conveyor systems can be a productivity multiplier on construction sites—especially where access is tight, the haul route is repetitive, and you want to reduce double-handling. But they can also become a constant source of spillage, mistracking, and downtime if the material is unpredictable, the incline is too steep, or the setup is treated as “temporary” in all the wrong ways.

This guide helps you decide where belt conveying fits on Sydney construction jobs (and similar Australian conditions), where it doesn’t, and what makes the difference between a smooth-running line and a daily troubleshooting session.

Where belt conveying fits best on construction sites

Belt conveying performs best when the job involves consistent, repeated movement—moving material steadily from A to B without stop-start machine cycles.

It’s often a good fit when you’re dealing with:

- Bulk spoil removal during excavation

- Sand, aggregate, and crushed material are transferred to stockpiles

- Feeding a screen, crusher, mixer, or hopper with a steady flow

- Long runs where repeated loader travel creates congestion and delays

- Sites where reducing machine traffic improves safety and logistics

A major benefit on active sites is traffic reduction. If a belt line can replace dozens (or hundreds) of loader cycles, it can reduce interaction risk and free up space for other trades—provided you can establish safe zones around the equipment.

Question: Is belt conveying only for big sites?

No. It’s less about site size and more about whether you have a repeatable material-movement problem. Smaller sites with tight access, basements, or long carry distances can still benefit—if feeding is controlled and safety controls are realistic.

Where belt conveying doesn’t fit (or needs heavy planning)

Belt conveying is less forgiving than many people expect. If you can’t control feeding, alignment, and housekeeping, small issues compound quickly.

It’s often a poor fit when you have:

- Highly variable demolition waste (rubble mixed with timber, rebar, plastic)

- Oversized lumps that bridge at hoppers and transfer points

- Very wet or sticky spoil (carryback, build-up, tracking issues)

- Short-duration tasks where relocation time kills productivity

- Sites where you cannot implement proper guarding/exclusion zones

- Steep elevation changes that push the belt beyond practical incline limits

None of these are automatic “no” answers—but they do mean you need a more engineered approach (screening, controlled hoppers, better transfers, more cleaning capacity) to keep the line reliable.

Question: What materials suit belt conveying best on-site?

Generally, it’s easiest with materials that are:

- Free-flowing: sand, aggregate, crushed rock

- Consistent in lump size

- Not overly wet or sticky

- Low in contamination (minimal rebar/timber/plastics)

Wet clay and mixed demolition can be handled, but success depends heavily on feed control, belt cleaning, and transfer design.

Construction applications where belt conveying usually wins

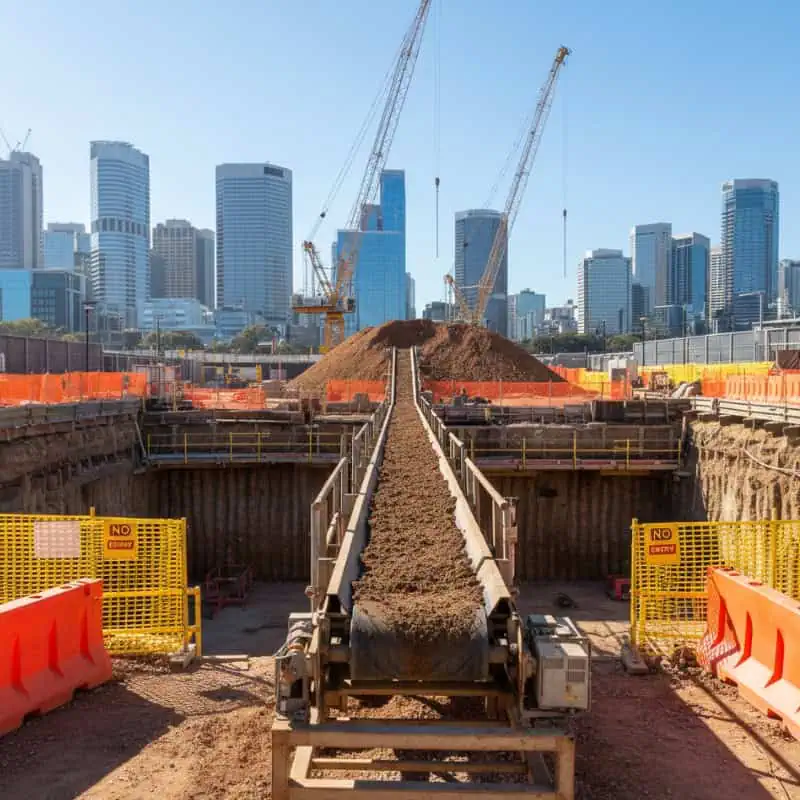

Confined-access and basement spoil removal

This is one of the strongest use cases. Sydney residential and commercial jobs often involve narrow access, limited laydown, and strict street interfaces. A belt line can:

- Reduce repeated machine passes in tight zones

- Create a predictable spoil-out pathway

- Lower surface damage risk from constant plant travel

- Keep the workforce clearer by moving spoil continuously

The key is consistent feeding. If spoil is dumped in irregular “slugs,” you’ll see surging, spillage, and stoppages. A buffering hopper and disciplined loading approach are what turn this into a reliable system.

Trenching runs and backfill transfer

For services trenching, bedding sand and backfill aggregate often need to move along a consistent line. A belt setup can reduce double-handling and help when the stockpile is separated by fencing, traffic routes, or other trades.

Stockpiling and consistent feed to the plant

Belts shine when feeding screening/crushing or other downstream equipment. A steady feed reduces surges that cause blockages, spillage, and uneven output.

If you want a quick overview of typical configurations and considerations, start with these conveyor solutions for construction sites.

Portable vs fixed setups: a practical decision

Construction sites tend to favour portable/modular systems because workfaces move and programmes change. The decision is usually about stability vs flexibility.

Portable/modular fits when

- The job is staged, and you’ll shift discharge points over time

- The route will be interrupted by other trades or site changes

- You need to pack down quickly for movements or programme phases

- Distances and inclines are moderate and manageable

Fixed or semi-fixed fits when

- The route remains stable for weeks/months

- You’re feeding the plant continuously

- You can justify engineered transfer points, better guarding, and platforms

- Downtime risk is high enough to warrant a more robust install

The constraints that make or break site belt conveying

Most site failures trace back to a handful of predictable constraints. Spot them early, and you’ll save days of downtime.

1) Feeding and flow control

Belts love consistent feed. Construction sites love inconsistent dumping.

Symptoms of poor feed control include:

- Spillage at loading points

- Material rollback

- Sudden belt strain and mistracking

- Dust surges when fines puff during overloads

Practical improvements:

- Use a hopper to buffer dumping and meter feed

- Reduce drop height and control impact at the load zone

- Keep feed centred—off-centre loading creates tracking problems fast

2) Inclines and elevation change

Incline is a common “silent problem.” Push the angle too steep, and you’ll see rollback, slip, and unstable transport.

If your run needs a significant climb:

- Break elevation change into staged transfers

- Design load and skirting to stabilise the material stream

- Confirm the setup suits the duty—selecting the right conveyor system options matters here

3) Transfer points

Transfers are where belts win or lose reliability—especially with inconsistent site material.

Common problems:

- Spillage from poor chute geometry

- Blockages from oversized lumps or wet fines

- Dust clouds from uncontrolled drops

- Accelerated wear at impact zones and skirt interfaces

Better transfer points are:

- Easy to inspect and clean

- Built to centre and slow the stream

- Designed for wear (liners, replaceable wear components)

4) Carryback and housekeeping

Carryback (material sticking to the belt and returning past discharge) is manageable with clean aggregate but can explode in wet/sticky conditions.

When carryback gets out of control:

- Build-up forms on pulleys/idlers

- Tracking deteriorates

- Cleanup workload rises sharply

- Slip and performance issues appear

Carryback management usually requires:

- Effective belt cleaning (primary/secondary as needed)

- Correct tension and alignment

- Scheduled safe housekeeping routines (because no cleaner is perfect)

Question: Why do belts mistrack so often on construction sites?

Because construction creates the perfect storm:

- Uneven foundations and settlement

- Mobile setups that aren’t squared/levelled consistently

- Off-centre feeding from plant dumping

- Build-up on pulleys and return runs

- Damage from contamination

If mistracking is persistent, treat it as a system issue: alignment, loading, and build-up first—then rollers and adjustments.

Safety essentials on active Sydney/NSW sites

Belt conveying introduces hazards that must be managed like any other plant: nip points, entanglement risk, unexpected start-up, transfer pinch hazards, and maintenance/cleaning exposure.

At a minimum, site planning should cover:

- Guarding for moving parts and pinch points

- Exclusion zones that reflect real site foot traffic

- Emergency stops that are accessible and tested

- Clear isolation/lockout procedures for cleaning and maintenance

- Competency and supervision for operators and nearby workers

SafeWork NSW’s code of practice on managing plant risks is a useful reference point for expectations around controls, safe systems, and maintenance, managing the risks of plants in the workplace.

Industry also commonly references AS 1755 when discussing conveyor safety and guarding principles in Australia (without reproducing the standard itself).

Question: Is belt conveying safer than using loaders everywhere?

It can be—particularly if it reduces machine travel in tight spaces and lowers traffic interaction risk. But it introduces different hazards. The safer option is the one you can control well with guarding, exclusion zones, and a clear safe system of work.

A quick “fits/doesn’t fit” framework

Before committing, run through this:

Site and access

- Can you keep a stable route that won’t be blocked constantly?

- Can you create safe exclusion zones around the belt and transfers?

- Do you have space for a proper loading zone (not improvised dumping)?

Material reality

- Is the material consistent enough to avoid constant blockages?

- Is contamination likely?

- Will wet conditions create carryback and build-up?

System reality

- Is the incline realistic?

- Are transfer points properly controlled?

- Who owns daily checks, cleaning, and isolation?

If you answer “no” to several, belt conveying may still be possible—but it will require more engineered controls and more disciplined operations.

How to make belt conveying work better in construction conditions

If belt conveying fits your job, reliability comes down to discipline and setup quality.

Stabilise the structure

- Make supports stable—don’t sit on loose fill

• Square and align the line before production starts

• Re-check after rain, relocation, or heavy loading

• Keep the load centred to reduce tracking issues

Engineer the load zone

Even modest improvements pay off:

- Controlled feed via hopper/buffering

- Reduced drop height to limit impact and dust

- Skirting and sealing that reduce spillage

Plan cleaning and housekeeping

Assume you need:

- Pre-start checks and mid-shift inspections at transfers

- End-of-day housekeeping (with isolation)

- A routine for carryback management

If you’re repeatedly cleaning carryback, treat it as root-cause—often cleaning systems, tension, and build-up need attention.

For equipment context and configuration ideas relevant to site work, see these conveyors for moving construction materials.

Common mistakes that create downtime

- Treating belt conveying like a wheelbarrow replacement (instead of a controlled system)

- Underestimating wet clay and fines carryback

- Improvised transfer points that constantly spill

- Poor foundations leading to recurring mistracking

- Weak safety controls because the setup is “temporary”

- No daily testing of emergency stops and isolation practices

FAQ

When is belt conveying the best choice on a construction site?

When the route is repeatable, the material stream can be controlled, and the job duration justifies setup—especially where tight access or congestion makes loader-only handling inefficient or risky.

When should you avoid it?

When material is heavily contaminated or highly variable, feeding can’t be controlled, the incline is too steep for stable transport, or you can’t implement realistic guarding and exclusion zones.

Can it handle wet clay?

Sometimes, but wet clay often drives carryback, build-up, and tracking issues. Success depends on belt cleaning, transfer design, and disciplined housekeeping.

What causes the most downtime on construction belts?

Inconsistent feeding and poor transfer control—these drive spillage, blockages, tracking issues, and accelerated wear.

What safety controls matter most?

Guarding of nip points, accessible emergency stops, isolation/lockout for cleaning and maintenance, and exclusion zones that match how people actually move on site.